Sextortion

Help Us Locate Additional Victims of an Online Predator

Ashley Reynolds was a happy 14-year-old who loved sports, did well in school academically and socially, and enjoyed keeping a journal she intended her “future self” to read. But what happened in the summer of 2009 was so devastating that she couldn’t bring herself to record it in her diary—or speak about it to anyone.

She had become the victim of sextortion, a growing Internet crime in which young girls and boys are often targeted. Her life was being turned upside down by an online predator who took advantage of her youth and vulnerability to terrorize her by demanding that she send him sexually explicit images of herself.

After several months, Ashley’s parents discovered what was happening and contacted the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). Ashley and her parents later supported the FBI investigation that led to the arrest of 26-year-old Lucas Michael Chansler, who last year pled guilty to multiple counts of child pornography production and was sent to prison for 105 years—but not before he used the Internet to victimize nearly 350 teenage girls. The majority of those youngsters have not yet been identified.

That’s why the FBI is requesting the public’s help—and why Ashley has come forward to tell her story—so that Chansler’s victims can be located and will know, as Special Agent Larry Meyer said, “that this dark period of their lives is over.”

Meyer, a veteran agent in the FBI’s Jacksonville Division who investigates crimes against children, explained that 109 of Chansler’s victims have been identified and contacted so far, leaving approximately 250 teens “who have not had closure and who probably haven’t obtained counseling and other help they might need.” He noted that Ashley is a brave person with a supportive family “and has been able to use this experience to make her stronger.” Unfortunately, that has not been the case for all the girls, some of whom have dropped out of school and tried to end their lives.

Help Us Locate Victims

Lucas Michael Chansler victimized nearly 350 teenage girls over a several-year period ending in January 2010. To date, the FBI has identified and located 109 of those victims and is actively working to identify others to help provide them closure and assistance. If you have information that may help identify victims of Lucas Michael Chansler—or if you believe you may have been victimized by him—please complete our Office for Victim Assistance’s confidential questionnaire.

Chansler, who was studying to become a pharmacist, used multiple personas and dozens of fake screen names—such as “HELLOthere” and “goodlookingguy313”—to dupe girls from 26 U.S. states, Canada, and the United Kingdom. And he used sophisticated techniques to keep anyone from learning his true identity.

Pretending to be 15-year-old boys—all handsome and all involved in skateboarding—he trolled popular online hangouts to strike up relationships with teenage girls. In one instance on Stickam, a now-defunct live-streaming video website, evidence seized from his computer showed four girls all exposing their breasts. “The girls are apparently having a sleepover, and Chansler contacted one of them through a random online chat,” Meyer said. “These girls thought they were having a video chat session with a 15-year-old boy that they would never see or hear from again, so they are all exposing themselves, not realizing that he is doing a screen capture and then he’s coming back later—very often in a different persona—saying, ‘Hey I’ve got these pictures of you, and if you don’t want these sent to all your Myspace friends or posted on the Internet, you are going to do all of these naked poses for me.’”

Don’t Become a Victim of Sextortion

Special Agent Larry Meyer and other investigators experienced in online child sexual exploitation cases offer these simple tips for young people who might think that sextortion could never happen to them:

- Whatever you are told online may not be true, which means the person you think you are talking to may not be the person you really are talking to.

- Don’t send pictures to strangers. Don’t post any pictures of yourself online that you wouldn’t show to your grandmother. “If you only remember that,” Meyer said, “you are probably going to be safe.”

- If you are being targeted by an online predator, tell someone. If you feel you can’t talk to a parent, tell a trusted teacher or counselor. You can also call the FBI, the local police, or the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s CyberTipline.

- You might be afraid or embarrassed to talk with your parents, but most likely they will understand. “One of the common denominators in the Chansler case,” Meyer noted, “was that parents wished their daughters had told them sooner. They were very understanding and sympathetic. They realized their child was being victimized.”

“It went from what would be relatively benign pictures to fulfilling Chansler’s perverted desires,” Meyer said, adding that while adults know that a young person’s life is only beginning in high school, “to a 13- or 14-year-old girl, thinking that all her friends or her parents might see a picture of her exposing her breasts, the fear was enough to make them comply with Chansler’s demands, believing they had no better options.”

When FBI agents interviewed Chansler after his arrest, they asked why he selected that age group. “One of the comments he made,” Meyer said, “was that older girls wouldn’t fall for his ploy.”

Ashley fell for Chansler’s ploy in late 2008 when she was 14 years old. She was contacted online by someone who claimed to be a teenage boy with embarrassing sexual pictures of her. His screen name was CaptainObvious, and he threatened to send Ashley’s pictures to all her Myspace friends if she didn’t send him a topless image of herself. Without considering the consequences, she sent it. She didn’t think the boy knew who she was or anything else about her. Nothing more happened until the summer of 2009, when Chansler’s persona messaged again, threatening to post her topless picture on the Internet if she didn’t send him more explicit images.

She ignored him at first, but then he texted her on her cell phone. He knew her phone number and presumably where she lived. Somehow he must have hacked information from her social media pages. Chansler was relentless. He badgered her for pictures and continued to threaten. The thought of her reputation being ruined—and disappointing her parents—made Ashley finally give in to her tormenter.

The next few months were a nightmare as Ashley complied with Chansler’s demands. She was trapped and felt she couldn’t talk to anyone. She kept thinking if she sent more pictures, the monster at the other end of the computer would finally leave her alone. But it only got worse—until the day her mother discovered the images on her computer.

“I just remember breaking down and crying, trying to get my dad not to call the police,” Ashley said, “because I knew that I would end up in jail or something because I complied and I sent him the pictures even though I didn’t want to. I tried to think rationally, like this guy was threatening me. But I sent him the pictures, so that’s breaking the law, isn’t it? I am under age and I am sending him naked pictures of me. I didn’t want to go to jail.”

User Names and E-Mail Addresses Used by Lucas Michael Chansler

Lucas Michael Chansler used a variety of online screen names and personas on various platforms to fool his young victims into thinking he was a 15-year-old boy. If you recognize any of the below screen names or e-mail addresses Chansler used and think that you or someone you know may have been victimized by him, please complete our Office for Victim Assistance’s confidential questionnaire.

Still, she was relieved that she didn’t have to keep her secret any longer. And her parents were supportive.

Ashley’s mother did some research and contacted the NCMEC’s CyberTipline. An analyst researching the case was able to tie one of the screen names used to sextort Ashley to another case in a different state and realized the predator most likely had multiple victims. Eventually, FBI and NCMEC analysts were able to pinpoint an Internet account in Florida where the threats were originating, and that information was passed to FBI agents who work closely with NCMEC in child exploitation investigations.

|

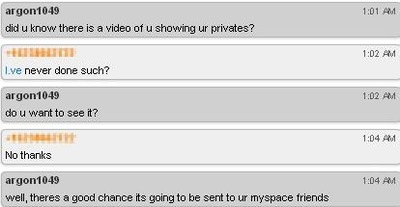

Part of an online chat between Lucas Michael Chansler |

When investigators executed a search warrant at Chansler’s Jacksonville house and examined his computer, they found thousands of images and videos of child pornography. They also found folders labeled “Done” and “Prospects” that contained detailed information about the nearly 350 teens he had extorted online.

Meyer and the Jacksonville Crimes Against Children Task Force analyzed the images of the girls to identify and locate them. One victim was located through a picture of her and her friends standing in front of a plate glass window at their school. Reflected in the glass was the name of the school, which led to her identification. Another victim was found through a radio station banner seen in a video hanging on her bedroom wall. The station’s call letters led to a city and, eventually, to the victim. More than 250 investigators, analysts, victim specialists, child forensic interviewers, and community child advocacy centers were involved in locating and interviewing the known victims.

But approximately 250 victims are still unidentified and may have no idea that Chansler was arrested and sent to jail.

“It’s important that we find these girls so that they don’t have to be looking over their shoulder, wondering if this guy is still out there and is he looking for them and is he going to be coming back,” Meyer explained, adding that “some of these girls, now young women, need assistance. Many probably have never told anyone what they went through.”

Ashley Reynolds, who was a victim of Lucas Michael Chansler’s sextortion scheme, hopes her story helps prevent other teens from falling for similar ploys.

Ashley, now 20, is doing what she can to get the word out about sextortion so that all of Chansler’s victims can be identified and other girls don’t make the mistakes that she made. “This ended for me,” she said, but for many of Chansler’s victims, “this never ended for them.”

When Meyer began working crimes against children cases eight years ago, he visited freshman and sophomore high school classes to talk about Internet safety. “Now,” he said, “we are going to fourth and fifth grade because kids are getting on the Internet at younger ages.”

He added, “We know that youngsters don’t always make sound decisions. Today, with a smartphone or digital camera, an individual can take an inappropriate picture of themselves and 10 seconds later have it sent to someone. Once that picture is gone,” he said, “you lose all control over it, and what took 10 seconds can cause a lifetime of regret.”

For her part, Ashley hopes that talking about what she went through will resonate with young girls. “If it hits close to home, maybe they will understand. High school girls never think it will happen to them,” she said. “I never thought this would happen to me, but it did.”

For more information:

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children

- CyberTipline